- #White day a labyrinth named school not receiving texts full#

- #White day a labyrinth named school not receiving texts professional#

The executive suite seemed within their grasp, but they just couldn’t break through the glass ceiling.” The metaphor, driven home by the article’s accompanying illustration, resonated it captured the frustration of a goal within sight but somehow unattainable. In 1986 the Wall Street Journal’s Carol Hymowitz and Timothy Schellhardt gave the world an answer: “Even those few women who rose steadily through the ranks eventually crashed into an invisible barrier. What is to blame for the pronounced lack of women in positions of power and authority? Just seven companies, or 1%, of Fortune magazine’s Global 500 have female CEOs. In the 50 largest publicly traded corporations in each nation of the European Union, women make up, on average, 11% of the top executives and 4% of the CEOs and heads of boards.

The situation is not much different in other industrialized countries.

Most notably, only 2% of the CEOs are women, and only 15% of the seats on the boards of directors are held by women. Consider the most highly paid executives of Fortune 500 companies-those with titles such as chairman, president, chief executive officer, and chief operating officer. Despite years of progress by women in the workforce (they now occupy more than 40% of all managerial positions in the United States), within the C-suite they remain as rare as hens’ teeth. Because people with the best of intentions have misread the symptoms, the solutions that managers are investing in are not making enough of a difference. This is the situation regarding the scarcity of women in top leadership. If one has misdiagnosed a problem, then one is unlikely to prescribe an effective cure. The remedies proposed-such as changing the long-hours culture, using open-recruitment tools, and preparing women for line management with appropriately demanding assignments-are wide ranging, but together they have a chance of achieving leadership equity in our time.

#White day a labyrinth named school not receiving texts professional#

Pressures for intensive parenting and the increasing demands of most high-level careers have left women with very little time to socialize with colleagues and build professional networks-that is, to accumulate the social capital that is essential to managers who want to move up. For instance, married mothers now devote even more time to primary child care per week than they did in earlier generations (12.9 hours of close interaction versus 10.6), despite the fact that fathers, too, put in a lot more hours than they used to (6.5 versus 2.6). Vestiges of prejudice against women, issues of leadership style and authenticity, and family responsibilities are just a few of the challenges.

#White day a labyrinth named school not receiving texts full#

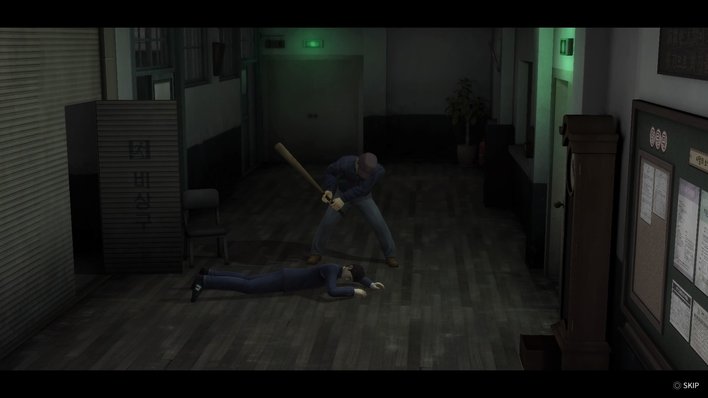

Routes to the center exist but are full of twists and turns, both expected and unexpected. Passage through a labyrinth requires persistence, awareness of one’s progress, and a careful analysis of the puzzles that lie ahead. Rather than depicting just one absolute barrier at the penultimate stage of a distinguished career, a labyrinth conveys the complexity and variety of challenges that can appear along the way. A labyrinth is a more fitting image to help organizations understand and address the obstacles to women’s progress. In fact, it leads managers to overlook interventions that would attack the problem at its roots, wherever it occurs. Eagly and Carli, of Northwestern University and Wellesley College, argue in this article (based on a forthcoming book from Harvard Business School Press) that the metaphor has outlived its usefulness. Two decades ago, people began using the “glass ceiling” catchphrase to describe organizations’ failure to promote women into top leadership roles.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)